BALTIMORE | Land, Food, and Community

A Collaboration with Harold Morales, Plantation Park Heights Urban Farm, Black Church Food Security Network, and Govans Market

Baltimore’s residential racial segregation created a lack of access to healthy foods, pre-existing health disparities, and higher rates of COVID-19 for its communities of color. During the early stages of the pandemic, a collective fe also prompted many to stock up on food leaving grocery shelves eerily empty. Spiritually and morally inspired organizations stepped up to provide food and supplies and workshops on gardening as meditative practice. In partnership with Plantation Park Heights Urban Farm and others, we asked: what role does food play in our visions of what the “good life” can be after the pandemic?

Planting a seed, we are reminded by members of the Black Church Food Security Network, is a kind of prayer, a hope in our future. Our GoodLife Project in Baltimore helped to support gardening, free food distribution, and food art by Plantation Park Heights Urban Farm and others. Rather than return to a “normal” that was unhealthy for communities of color before the pandemic—and worsened during the crisis—we must reevaluate our relationship to food and critique unjust food systems and their resulting health disparities. A new generation of collaborative work will be needed to improve food access, health, and our quality of life in Baltimore.

Religion in Baltimore

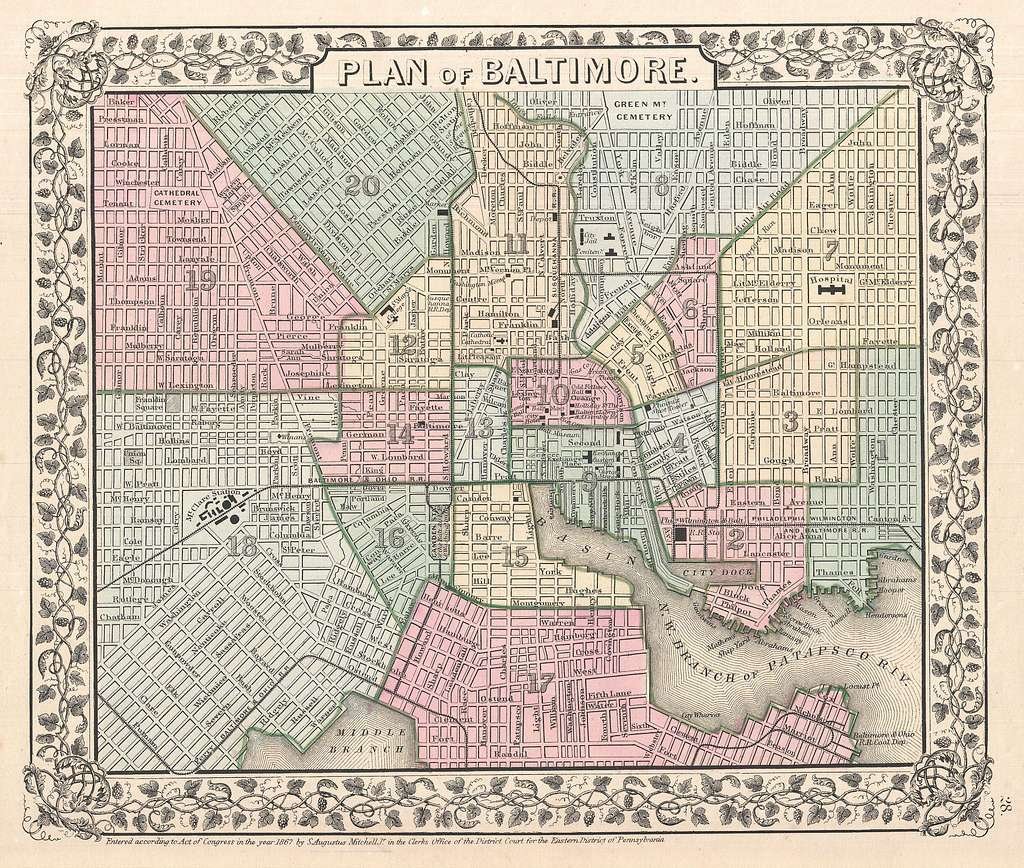

The westernmost port city on the eastern shore and 40 miles north of the US capital, Baltimore is on “middle ground.” The humid subtropical climate land was used as hunting grounds by the Yaocomico, of whom little is known by the 17th century, likely due to white settler colonialism and disease. The port facilitated a steady flow of migration and commerce from Europe and became a hub for trade between the north and south. Johns Hopkins, the city’s largest employer today, amassed much of its wealth through B&O investments to facilitate transport of goods produced through slave labor in the south to the north. The city’s ecological relationship to white settler racial capitalism led to several expansions, including visions and investments in infrastructure for 1 million inhabitants. The ebb and flow of residential racial segregation and desegregation movements, however, led to white flight and the city’s depopulation. Unable to keep up with the maintenance required of a built environment designed for a population twice its current size, the city’s racially inequitable concentration of resources took the geographic shape of a well resourced White L and resource-scarce Black Butterfly. Lack of access to healthy foods in concentrated areas led to higher rates of diabetes, heart disease, and other “pre-existing conditions,” which in turn led to higher rates of COVID-19 infections among communities of color.

Images from the Project

Suggested Readings & Resources

Matthew A. Crenson, Baltimore: A Political History (Johns Hopkins University Press: 2019)

Farm Alliance of Baltimore, “Farmers Feeding Baltimore” (2018)

Sheilah Kast and Melissa Gerr, “On Middle Ground: The History of Baltimore’s Jewish Community,” WYPR (February 18, 2019)

Pew Research Center, “Adults in the Baltimore metro area,” Religious Landscape Survey (2014)

Antero Pietila, Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City (Rowman & Littlefield: 2010)

Plantation Park Heights Urban Farm Short Documentary, YouTube (2022)

Elizabeth Rule and the Guide to Indigenous Lands Project in Partnership with Ashley Minner, Guide to Indigenous Baltimore, PocketSights

Urban Institute Report, "The Black Butterfly": Racial Segregation & Investment Patterns in Baltimore (2019)

Meet the Team

Dr. Harold Morales

Dr. Harold D. Morales's work is largely inspired by his family's spiritual roots in Central America and diaspora experience in Los Angeles. He draws on these to better understand and work in solidarity with marginalized communities. His research and teaching focuses on the intersections between race and religion and between lived and mediated experience. He uses these critical lenses to engage Latinx religions in general and Latino Muslim groups in particular. Dr. Morales is now focusing on developing public scholarship initiatives through his research on mural art and social justice issues in the city of Baltimore and through the Center for the Study of Religion and the City which is generously supported by the Henry Luce Foundation.

@hrdMorales (Twitter)

-

Ariel Mejia

Ariel Mejia (she/her) received her B.A. in Global Studies and Social Impact with a minor in African/African American Studies from Grand Valley State University. She is currently pursuing her M.A., in Africology/African American Studies at Eastern Michigan University. Her research interests include African History (primarily the Namibian genocide), the African Diaspora, and Gentrification & Food apartheid. Her overall goal is to obtain a PhD and eventually establish a non-profit organization.

-

Natalia De Jesus Torres

Natalia De Jesus Torres (she/her) served as a research fellow for the CRCs Baltimore based Good Life Project and as the secretary for Morgan State University's Latin/x Student Association (LSA) for the 2020-2021 academic year. Natalia is currently a senior at Morgan State University studying Civil Engineering, where she plans to use her knowledge of structural design and construction to eventually help build sustainable infrastructure and plans to study project management in the future to understand how to effectively work collaboratively to develop innovative designs and projects.

-

Safiyah Cheatam

Safiyah Cheatam (she/her) has dedicated nearly a decade toward youth engagement in arts education in Baltimore City, wherein she is currently the Assistant Manager of Teen Programs at the Walters Art Museum. She received a Masters of Fine Arts from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC).

-

Santana Alvarado

Santana Alvarado (they/them) graduated from CUNY Hunter with a B.A. in Sociology and a minor in Music. Santana is passionate about reindigenizing the arts, education, youth programs, and queer spaces. They have dedicated themselves to BIPOC religious and community organizations. Like their namesake, Santana enjoys playing guitar and writing songs that center justice, liberation, and intimacy with the Divine.

Statement of Gratitude

Our Good Life Project was seeded by Harold Morales, Rupa Pillai, and Kayla Wheeler with support from Amrita Bhandari, Ariel Mejia, Sierra Lawson, Fatima Bamba and many others from the Center for Religion and Cities’ collective.

The work is supported through generous funding from Morgan State University and the Henry Luce Foundation.

The city of Baltimore is located on the traditional and unceded lands of the Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannock peoples and Algonquian-speaking peoples of the Cedarville Band of the Piscataway Conoy, the Piscataway Indian Nation, and the Piscataway Conoy Tribe, who continue to live in the city. The CRC invites you to join us to learn about the Indigenous history of and contemporary context of Native groups in the lands we live and work on.